McREL

Our expert researchers, evaluators, and veteran educators synthesize information gleaned from our research and blend it with best practices gathered from schools and districts around the world to bring you insightful and practical ideas that support changing the odds of success for you and your students. By aligning practice with research, we mix professional wisdom with real world experience to bring you unexpectedly insightful and uncommonly practical ideas that offer ways to build student resiliency, close achievement gaps, implement retention strategies, prioritize improvement initiatives, build staff motivation, and interpret data and understand its impact.

Recently I participated in a Webinar titled “Opportunities and Challenges for Web 2.0 in Schools” given by Tech & Learning Magazine. One of the hosts was Alan November. He brought up a very intriguing myth about educational technology that really made me think. The myth is that educational technology broadens the perspectives of students by giving them greater access to a wide range of thoughts, ideas, and opinions online. Until recently, I believed in this myth. But after hearing Alan’s explanation, I realized I could be wrong. Essentially, he said that the myriad of choices on the internet make it possible for people to pigeonhole themselves into narrower and narrower points of view. While choices abound, students are selecting sources (blogs, social networks, list services, & news sites) that match their current outlook on the world. Rarely are they experiencing different points of view and incongruent perspectives. In the old days of three major news networks and town news papers, people were forced to see and hear about information that was foreign to their way of thinking and world view. Now, if you are so inclined, you can easily ignore most information other than the views you want to hear. As Alan November put it, some people are fans of the Huffington Post and some are fans of Fox News, rarely do they experience each others ideas.

Coincidentally, the next day I read about a new report by the Pew Hispanic Center called “Sharp Growth in Suburban Minority Enrollment Yields Modest Gains in School Diversity” (http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=105). It said while African Americans and Asians are becoming slightly less segregated, Latino students were becoming more segregated in U.S. suburban schools. One of the possible causes cited was the proliferation of schools of choice that offer customized programs, themes, and curricula around Latino culture and language. Many Latino families are self-selecting these unique schools for their children. Of course, this tends to concentrate and segregate them. Now I have always been a proponent of school choice. I believe that it results in more innovation, customer satisfaction, and accountability. However, choice, in educational technology or school enrollment, seems to have the unintended consequence of segregating some groups of students.

Diversity in our schools seems to be suffering from both self-selected incidents of segregation, and segregation of thought as students constrict their online experiences to just those ideas and opinions that affirm their current beliefs. So what can we do about it? One answer is simply good teaching. One of the best classroom strategies for opening student minds to the world is Identifying Similarities and Differences. Using this strategy, teachers can help students understand other points of view and encourage classroom dialogue and debate about ideas, cultures, and perspectives that cause students to think and revise their developing views.

History tells us that segregating ourselves is not good for society. Yet school and online choice have strong merits. How can we enjoy the benefits of choice without the pitfalls of segregation?

Written by Matt Kuhn.

Most of the students we teach today are in the Millennial Generation (born from 1982-2001). According to demographers, these students (who are between the ages of about 7 and 26), are comparatively optimistic, confident, achieving, pressured, and cooperative team players. Millennials have become a generation of positive trends in educational achievement. Millennial’s aptitude scores have risen within every racial and ethnic group.

One Millennial in five has at least one immigrant parent. Thanks to immigration surges, Millennials have become, by far, the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in U.S. history. Yet, they tend to ostracize outsiders and compel conformity. Millennials feel more of an urge to homogenize, to celebrate ties that bind rather than differences that splinter. Millennials are less inclined than GenXers were at a similar age to take big career risks. They have a fear of failure, aversion to risk, and desire to fit in to the mainstream.

For Millennials, “collaborative learning” has become as popular as independent study was for Boomers or open classrooms for Gen Xers. Surveys confirm that Millennials don’t mind a more structured curriculum, more order, more stress on basics. They grew up in the standards era. It’s how the standards are taught, not so much what they are, that seems to matter most to Millennials.

Recently, the news reported that 2007 broke a record for the number of births in the United States and that 40% of them were by out-of-wedlock parents. This new “baby boom,” combined with uncertainty the nation faced after 9-11 and the current economic recession will shape the newest generation born 2002-present. These students are our 6 and 7 year olds in school now. So what types of instructional strategies will resonate most with this new generation? Will they still love collaborative learning as much as Millennials or will they go a different way? What will distinguish them from students in previous generations? For those of you teaching this new generation in kindergarten, first and second-grade classrooms, have you noticed any differences among them and their older peers?

Written by Matt Kuhn.

Working as a consultant, there are many aspects of my job. I travel across the country to big cities and tiny towns to facilitate professional development sessions with teachers. I conduct technology audits to help districts align their mission and vision with the tools that teachers and students have available. There are other times, as with any job, where I’m sitting at an airport late on a Friday evening or filling out a time sheet, that feel a little less grand, however necessary they may be.

Sometimes, though, you have those BIG moments…the ones that give you chills, remind you why you go into the office or board tiny planes for a living…the ones you know you will take home and share with your family at the dinner table that evening. I had one of those moments the other day that I know I will remember forever. I was in North Dakota, working with a group of early childhood teachers, helping them to create accounts on our online community. Some of them were extremely comfortable with the process, having joined numerous other Ning, Moodle, and other such sites before. Others needed a little more assistance. One older Native American woman, I noticed, didn’t seem to be typing anything. I went over to see if I could help.

As it turned out, she didn’t have an email address to enter into the registration form. She had never created an email account before. Finding the right person at her district who may have been able to give us her email account and password would have been too time-consuming, so we quickly created a Gmail account for her. She turned to me, pointing to the new address she’d carefully written down. “So this is my email address?” she asked. “That’s your email address,” I confirmed. She laughed a big, hearty laugh. “I can give this to my grandkids! They can email me!”

Later that afternoon on the flight home, I thought about that woman and all the doors that had just opened up for her. I pictured her sharing her email address with family members and friends and the excitement when she receives her first few responses. In a tiny, tiny, way, I made a difference in this person’s life. Moments like these are why I love what I do.

Come to think of it, I have a person I need to go email. ☺

In Rethinking Homework Part 1, I described how three chemistry teachers had made the decision to place their lectures on vodcasts, allowing students to listen at their own pace, while freeing class time for discussions, labs, and activities.

In another example of Rethinking Homework, Diana Laufenberg, from the Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia, engaged her students in President Obama’s address to Congress on February 24 using Gcast, a resource that lets you record a brief podcast using your cell phone. Students were given the assignment of watching the President’s speech, then recording a brief summary of their thoughts and questions regarding Obama’s stimulus plan. The students were likely relieved that they did not have to sit and write a reflection, but instead were able to use their cell phones to give initial reactions to the speech.

These two examples paint a very different picture of homework than a student struggling through a worksheet late in the evening at the kitchen table. They make homework purposeful, engaging, and leave class time for higher level discussions and activities. If homework looked this way more often, educators and students would likely have a much more positive opinion of the practice than they currently do.

What other best practices have you heard of that engage students and provide meaningful learning experiences outside of class time? What steps do school leaders and decision-makers need to take to broaden these types of experiences to all students? We welcome your comments and questions!

The combination of past classroom experiences and traditional university training conspire to keep many teachers behind the curve of new pedagogical techniques. Another impediment often occurs as new teachers are assimilated into a school’s culture. They frequently find that many innovative techniques they do want to try rub against the grain of the schools establishment.

For instance, many students learn about parts of speech in the same way I did when I went to school in the 1970s and 1980s by doing worksheets like the one below.

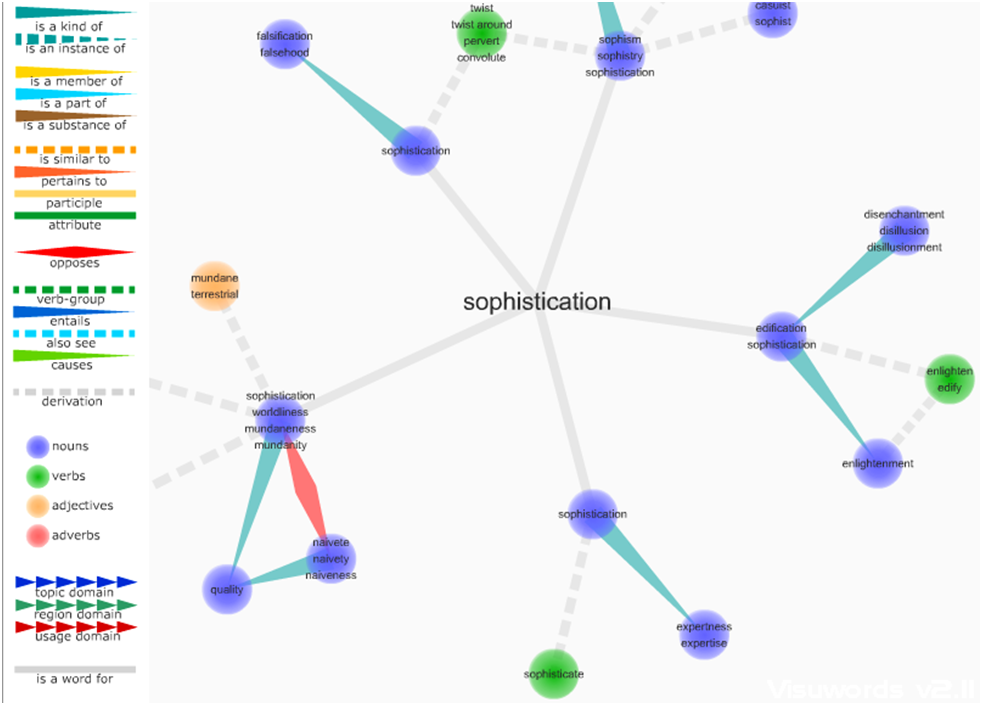

While this worksheet works fine for students with strong verbal/linguistic learning abilities, it does not work as well for student with other learning styles such as visual learners. Many graphic organizers are available online to complement or replace this activity. However, there is something even better. Dynamic or interactive web applications can allow students to evaluate multiple language connections and differentiates the learning in terms of both style and level of proficiency. One such resource is Visuwords at www.visuwords.com. Visuwords™ uses Princeton University’s WordNet, an opensource database built by University students and language researchers. Combined with a visualization tool and user interface built from a combination of modern web technologies, Visuwords™ is available as a free resource to all patrons of the web.” It allows students to check their own understanding of the parts of speech, edify their own writing, and see how language is a web of infinitely connected concepts. As you can see below, I entered the word “sophistication” and found the verb “edify,” which I just used to describe how students can benefit from using visuword.

I think one answer to better instruction is to combine proven instructional strategies like nonlinguistic representation- graphic organizer with interactive technological tools. Now I have two questions for you:

- What other modern tools can be combined with tried and true instructional strategies?

- What can be done to speed up the adoption of these tools by today’s teachers?

Written by Matt Kuhn.

You probably remember the television commercial—someone carrying a jar of peanut butter collides with someone holding a chocolate bar. At first, they’re angry with one another, until they taste their accidental creation and realize they’ve made an uncommonly good candy bar.

That’s a little like what happens here at McREL. We “mash up” top-notch researchers with experienced educators to generate new insights and uncommon sense about education. By taking rigorous research and blending it together with professional wisdom from experts, we create something more meaningful and reliable than either would be alone.

In our blog, you’ll hear a mix of voices. You’ll hear from our researchers, who have an uncanny knack for using data to analyze some of education’s most vexing challenges. And you’ll hear from our seasoned education experts, who combine creative thinking and practical experience to challenge conventional wisdom and come up with new insights to education problems.

We hope you’ll find that by blending our researchers’ command of regression analysis and data crunching with our education consultants’ experience with real-world breakthroughs and successes, that the result is something unexpectedly insightful and uncommonly practical in your work as educators.