As explored more deeply in our recent white paper, Student Learning That Works: How Brain Science Informs a Student Learning Model, the human brain works quite hard to help us filter out and forget extraneous information. This probably made good sense in the hunt-or-be-hunted days, but in the information age, forgetting is not a recipe for success.

Fortunately, once teachers know the stages of memory—and what happens between them—they can use some clever workarounds to help students strengthen recall. Essentially, we need to trick our brains into forgetting to forget.

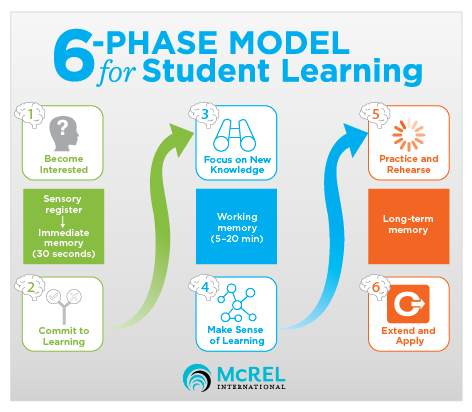

Starting with sensory register—the very first impression that a new stimulus makes on us—the stimulus may or may not proceed to immediate memory for about 30 seconds. From there it may or may not cling for survival in the working memory for 5–20 minutes. The final stop would be long-term memory.

So, what tactics can teachers exploit to help the original stimulus mature into a long-term memory? Here’s a summary of our six-phase model for student learning and the questions teachers should be asking themselves at each phase:

- Become interested. Why should students care? What will spark student interest?

- Commit to learning. What meaning will students find? What will motivate them to learn? What will connect them to the learning?

- Focus on new knowledge. What do I want students to think about? What will I show them? How will I help them visualize important concepts?

- Make sense of learning. How will I chunk learning and support information processing? What themes, categories, sequences, or links to prior learning do students need to make with this learning?

- Practice and rehearse. What knowledge and skills must students commit to memory or automate? What feedback will I provide to guide deep learning?

- Extend and apply. What will I ask students to do with their knowledge? How will I (and students) know they’ve mastered learning?

We all know memory can play tricks on us. Well, it’s time to turn the tables, and use our knowledge of the science of memory formation to help our students trick their minds into storing, connecting, and applying more of what they learn in school. Memory plus curiosity make for powerful, lifelong learning.