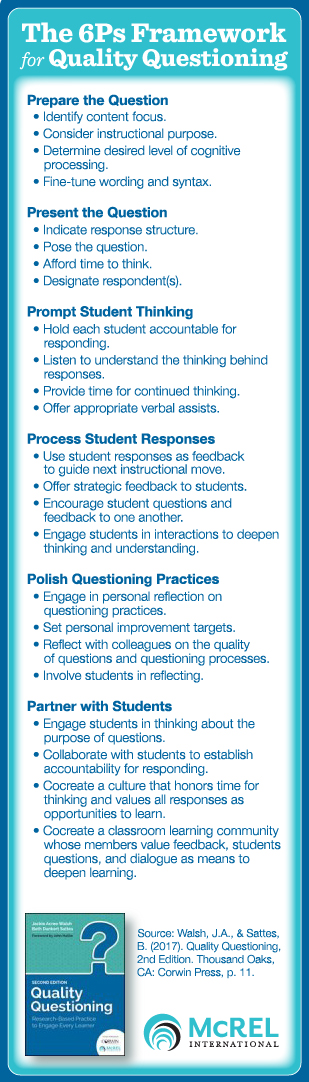

Quality questioning is a process that begins with prior planning and involves intentionality in questioning to activate thinking of all students throughout a class period. The “6Ps Framework,” presented in our book, gives definition to this process and serves as a tool for teachers to use in both planning for and reflecting on their questioning practice. Consider the planning questions embedded in the first four components of the Framework: What questions will I ask? How will I engage all students in responding? What cues, prompts, or scaffolds can I offer if students don’t respond completely or correctly? How can I engage students in dialogue that deepens their thinking?

Plan questions that help students connect to content. Too many classroom questions are inert. They fall flat because they fail to ignite student interest or curiosity, to focus student attention, or to communicate a purpose for thinking and responding. They don’t challenge student thinking because a large majority are at the simple recall level. Quality questions catalyze student thinking and engage them in connecting what they think they know to the focus of the question. They invite students to use surface knowledge as they develop deep understandings through problem solving, analyzing or evaluating an issue, creating a new and personal response, or posing a question or wondering. Such questions enliven a lesson and enable students to make their own meaning of the content. When teachers plan 2–4 such questions in advance of class, they take the first step in stimulating dialogue. All questions do not have to be formulated from scratch; you can modify existing questions to meet criteria for quality questions. Access a template you can use to create or adapt questions as part of your lesson design process—ideally through collaboration with colleagues.

Identify response structures that engage all. If we are to move beyond student volunteers responding to our questions one at a time, we must select alternative response structures that are appropriate for our questions and our students. Paired response structures and other collaborative formats provide a context in which all students have opportunities to engage. The likelihood that all will participate in discussions increases when we select protocols that scaffold student participation. Think-Pair-Share provides a structure for pair response. Text-based protocols, including Save the Last Word for Me, scaffold participation and are appropriate for grades 5–12. Matching response structures with questions in advance of class—as a part of lesson design—is key to effective use. Without this advance planning, we too often revert to calling on those with their hands raised.

Be ready to prompt. As part of your lesson planning, anticipate possible student responses to your questions. Why is this be important? When we identify and share common student errors and misconceptions, we can prepare follow-up questions that help scaffold thinking, develop or deepen understanding, and keep a conversation going. Use a planning template designed to support collaborative thinking and planning that produces not only a quality question but also related prompts that we can keep in our hip pockets, just in case we need them.

Allocate time for student questions and dialogue. John Hattie reports that student responses to teacher questions average 2–3 words—or less than 5 seconds—70% of the time (2012, p. 73). He further notes that student questions are almost entirely absent from our classrooms. Think about your students. How many of them elaborate on ideas when responding? Raise their own questions? If the percentage is not as high as you’d like, it may be because so many of us do not make time and space for extended talk that might lead to student questions. We can begin by committing to use both think times 1 and 2—or “wait” times—pausing after questions are posed and before anyone (teacher or student) responds. This strategy affords everyone time to think about what they have to say in response to the initial question (think time 1). Pausing again after a student comment or response provides the speaker time to elaborate (going beyond the first 2–3 words that come to mind!) and gives other students time to process the speaker’s ideas and prepare a response or question (think time 2). Additionally, we can allocate time within our lesson designs for academic conversations, i.e., dialogue, to occur. If we value these outcomes, we need to plan for them.

Partner with students to help them understand the why of dialogue. Planning for the above four dimensions of quality questioning doesn’t ensure that students will engage. Many—we might say most—students choose to opt out of classroom discourse. They may not see the purpose for responding to questions or for engaging in dialogue with their peers. They may lack the skills to participate in extended dialogue. If teachers are to move from monologue to dialogue, students must buy into the shift. And teachers have to set new expectations, help students see the value of participation, and co-create with students a culture in which all students feel comfortable responding and voicing their ideas. Use this guidance for partnering discussions with your students.

It takes more than a magician’s wand to shift one’s classroom from a place where teacher monologue dominates to one where students’ voices are heard and valued. Such a transformation is a process that occurs over time when teachers engage in intentional planning and when they collaborate with their students to create a new set of norms for questioning and learning together.

Upcoming webinar on Quality Questioning

Register now for a free webinar hosted by McREL on February 28, 2017, presented by Jackie Walsh and Beth Sattes: “Quality Questioning: A Catalyst for Thinking and Learning.” Space is limited.