Teacher: You are floating down the Delaware River and you are seated behind George Washington. What do you hear, feel, smell, and see?

Students: I hear the waves crashing against the boat. I feel anxious and scared. I smell body odor. I see George’s white hair.

The next day, begin with a reminder of their imagined journey on the boat; then review and check for understanding. The students could have simply read a passage and answered questions about George Washington’s river crossing, but this simple immersive exercise promotes deeper relevance, engagement, understanding, problem-solving, comprehension, and retention.

Why does this exercise work so well?

Asking higher-order questions requires more time for students to think and articulate their answers, and can greatly extend classroom conversations and learning. When students are challenged with higher-order questions, they draw from their own experience to formulate their answers. In other words, their understanding becomes personalized. Thought-provoking questions not only encourage deeper discussions in the classroom, but also help students develop skills they can use in real-life decision making. Asking a variety of questions helps students actively and broadly engage with and deepen their understanding of the content. The questions invite students to respond based on their thoughts about the content, relying not just on basic recall but actual experience, helping students learn how to think rather than what to think.

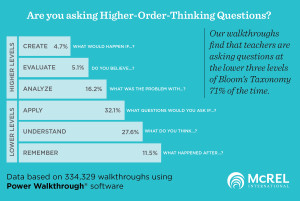

It’s a powerful instructional strategy, but classroom observation data collected with our Power Walkthrough system shows that teachers aren’t using higher-order questioning very often. In fact, we found that teachers are asking questions at the lower three levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy a whopping 71% of the time. Why might that be?

In the interest of time, teachers often perform a quick check for understanding, asking specific questions that require a simple right or wrong answer. Sometimes, teachers don’t know how to ask higher-order questions, or feel that they don’t have adequate time to generate more provocative questions during a lesson. Advance organizers can help students understand the expectations for each lesson and facilitate a higher level of classroom questioning. In Classroom Instruction That Works, 2nd ed. (2012), our McREL colleagues recommend asking inferential questions and using explicit cues to activate your students’ prior knowledge and develop deeper understanding of the content. You can also prepare sentence stems that help you craft higher order questions on the fly during classroom discussions.

Another way to focus classroom effort on higher-order questions that make learning memorable is to teach your students about the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, emphasizing how higher-order questioning promotes deeper learning. Once they have an understanding, they can then articulate at what level their questions are occurring. Try creating a poster of Bloom’s Taxonomy with your students for your classroom. Then, during classroom discussions, place a sticky note at the level of Bloom’s in which the students are working. This will help guide discussions, and serve as reminder for you and your students to stretch learning by reaching for the highest level of discussion. In our experience, most students would rather imagine themselves in a different time and place than sit and read a passage and complete a worksheet.

As a teacher or administrator, how have you inspired classroom curiosity through higher-order-thinking questions? Please share your great ideas.

Teachers need to make every lesson relevant and significant to every student. Have the students make the real-world connection, don’t do it for them.

I use real-life experiences to aid my students in higher order thinking.

I use an active process of analyzing, synthesizing, evaluating, reflecting, and applying how to think questioning to information toward specific situations and contexts.

For Science, we complete many hands on activities that lead to higher order thinking, especially when something does not go right in the lab. This allows us to question why this occurred and what could be done differently.

Hi Tony,

Thank you for your comment. I like the idea of having students create relevance to the material they are currently learning. Nice way to get them thinking a little deeper. (Sometimes with younger students we have to prompt them a bit to find the relevance.

Hello Antwanita,

That’s the best way to get buy-in and interest in the new learning. Thank you for your comment.

Hi Anice,

Thank you for sharing with us. Learning through failure is an excellent way to get to the higher-order thinking we want for our students and science is ideal!

I use open-ended questions a lot and relate the lesson to real-life applications.

I use open-ended questions and real-life applications problems in my classes as much as possible.