The revolution in understanding school leadership that McREL launched in 2005—that principals can influence student achievement—is now so widely accepted that some researchers are saying it’s time to move beyond “whether” and focus on “how.”

That’s been on our minds ever since that first meta-analysis 16 years ago, when we identified 21 leadership responsibilities and 66 practices that are associated with student success and built them into our Balanced Leadership® professional learning program. Until then, principals were viewed as administrators, plain and simple: allies to educators, in that they fought for resources for educators to do their jobs, but they weren’t necessarily expected to also focus on aligning systems to improve student learning. For generations of school leaders, getting promoted was bittersweet because it was in many ways a career change, from education to management.

Today, it would be hard to find a school board that isn’t looking for principals to be “instructional leaders.” The challenge now is not getting people to agree with this basic proposition, but on what, exactly, “instructional leader” means. With schools and districts experimenting with various ways to integrate principals into instruction while also keeping the lights on, it’s no wonder principals can feel like their heads are spinning. Balanced Leadership is, in large part, an effort to remind principals that every school needs not just a leader, but a leadership team to share the responsibility—and joy—of leading for student learning.

The Wallace Foundation is another organization that’s been closely monitoring the status of principals, and we’re delighted by the emphatic tone of their new report, How Principals Affect Students and Schools. Highly effective principals can add the equivalent of several months of learning to the school year, the authors found.

How do they do it? By establishing good working relationships, which encourages teacher retention, and by being able to identify effective classroom practices: “Principals must be able to distinguish high- from low-quality pedagogical practices, producing meaningful variation in teachers’ observation ratings.” If teachers were evaluated by supervisors who didn’t understand their work, they wouldn’t be able to complete the circuit from evaluation to practice.

As society’s expectations of principals continue to evolve, so does our Balanced Leadership program. Where it once focused on the concept of instructional leadership, we’ve recently updated the program to include important findings and strategies from the world of improvement science, high-reliability organizations, and school improvement.

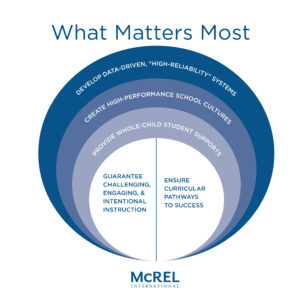

For example, we now incorporate our What Matters Most framework, which helps principals understand and act on five key levers for school and system improvement.

The revised program, which we now call Balanced Leadership for Student Learning, focuses on what knowledge, skills, and resources principals and system leaders need to have to support the five components of the What Matters Most framework, as well as leading and managing change, and developing a school culture in which all stakeholders take ownership for achieving equitable outcomes for every learner. It’s not a checklist oriented, one-size-fits all PD program, but rather it’s the forging of a creative mindset that can lead any school into excellence, within any local context.

What does this look like in practice?

When principals and leadership teams across the country (and internationally) partner with us, we begin by collaboratively discussing and assessing their school’s current initiatives in relation to the evidence-based practices revealed by What Matters Most. Once this foundational knowledge is in place, we then work together to identify the next logical actions they should take, based on their school’s own specific contexts, challenges, strengths, and goals. We link those actions to the key Balanced Leadership responsibilities and practices they’ll need to enact for success, and we provide professional learning and coaching to support their growth in these areas. Lastly, we help leaders create and enact a plan to lead, manage, and sustain the changes needed for school improvement and innovation efforts.

It’s important to note that principals can’t do this on their own. Every school has teacher leaders, too, and their voices need to be recognized and drawn into school improvement in a thoughtful way. Increasingly, we view a school’s “leadership” as being a team, not an individual.

That goes for district-wide, systems level leadership as well. Sustainable system-wide improvement requires collaboration, working together using a common leadership approach and language that isn’t confined to the walls of any particular school or office.

Kris Rouleau is the executive director of learning services and Kent Davis is the associate director of learning services at McREL International.