Earlier this year, I took my grandson to his first driver’s education class and memories came flooding back. When I was 15 years old and wanting to learn to drive, I turned to my oldest brother for instruction. With much effort and practice, I was ready to drive on the country roads in Iowa. I’ll never forget my calm brother’s sudden look of panic during a nighttime driving lesson after I mistakenly turned off the headlights as another car approached (I was trying to dim the headlights). Eventually, I graduated to driving on the highway, and, today, I’m a proficient driver.

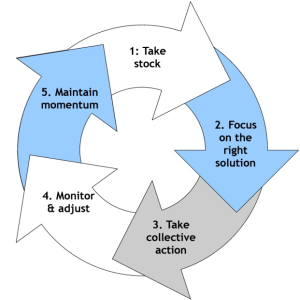

As I reflected on my experience of learning to drive, I realized how it aligns to a school’s improvement process. First, I took stock of the situation by considering the data: the people who could teach me to drive. Next, I focused on the right solution. Out of all the people I knew who could teach me to drive, I chose my oldest brother, who was the calmest and most patient. When I implemented my plan and approached my brother for instruction, I was taking collective action. Although I learned the basics of driving, my brother and I monitored and adjusted my driving as I improved. He continued to coach me in night- and highway-driving, and I maintained momentum by continuing to practice and improve my skills (and by baking chocolate chip cookies for my brother to celebrate our progress).

Schools use this same continuous improvement process for their improvement initiatives. A school first takes stock by collecting data to clearly identify the problem it faces. Next, the school identifies a focused, manageable improvement initiative that addresses and resolves the identified problem (see my earlier post about focusing on fewer, not more, initatives for success). After determining the right solution, the school takes collective action by developing a plan and timeline for engaging all staff members in ownership of the plan. The school identifies professional development needs, and collectively implements the plan of action with consistency and fidelity. A very important, though frequently omitted, step in the continuous improvement process is constant monitoring of the extent of implementation and its impact on student achievement, which enables mid-course corrections. Finally, the school maintains momentum of the improvement initiative by celebrating and sustaining the effort. This entire process allows the school to identify the successes and the challenges that arose, informing the process for the next initiative to be tackled.

We sometimes think that school improvement is a complex, difficult task. But if we break it down into a manageable, systemic process, we can confidently, collectively, and successfully take the wheel and move on down the road of improvement.

Here’s a diagram that illustrates this approach.

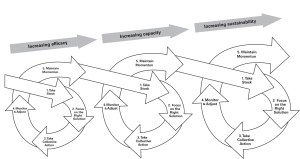

Here’s a diagram that illustrates this approach.